By DeLaynie Holton, Emily Dickinson Museum Intern

Emily Dickinson’s most extensive correspondence was with her sister-in-law, lifelong friend, and potential romantic interest, Susan Huntington Dickinson. Throughout her life, Dickinson sent over 250 poems to Susan, who lived next door in The Evergreens from 1856 through the end of her life. Susan was raised by her sisters following the death of her mother in 1835, splitting her time between Geneva, New York, Amherst, and Baltimore, where she taught mathematics for a time. While in Amherst during her youth, she developed a close friendship with Emily and, subsequently, the rest of the Dickinson family. She became engaged to Emily’s brother Austin Dickinson in 1853, and the couple moved into The Evergreens after their marriage three years later.

Emily and Susan’s vibrant, affectionate correspondence was deeply literary in subject and tone. Emily’s writing and revising process is apparent in the exchange of poems and letters as well. Emily sent Susan many drafts and variations of poems and even accepted editorial feedback – evidenced at least once with their discussion of “Safe in their Alabaster Chambers” (Fr124). Their letters included allusions to frequent visits and shared interests. A reader and writer herself, Susan would often exchange books and ideas with Emily. At the end of Emily’s life in 1886, Susan prepared her body for burial and wrote a heartfelt obituary for the Springfield Republican. With Susan as the inspiration for many of Emily’s poems and the sole recipient of even more, it is clear that the two women shared an intimate, loving, and life-long relationship. For more information on Susan visit Susan Huntington Gilbert Dickinson.

Below you’ll find a selection of poems Emily sent to Susan. The compiled correspondence between Emily and Susan can be found in Open Me Carefully by Ellen Louise Hart and Martha Nell Smith. The linked manuscripts are the versions sent to Susan and may differ from the text in the Franklin Reading Edition.

1858

This poem might have been carried to Susan on the path linking The Evergreens and the Homestead, the neighboring homes of the Dickinsons. With the houses next to each other, the lives of the inhabitants were closely intertwined.

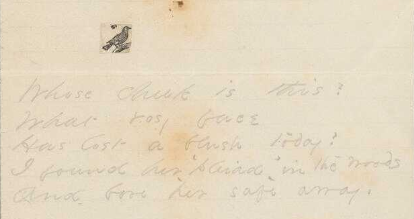

- “Whose cheek is this?” (Fr48)

1859

Sent to Sue with a flower and a small picture of a bird clipped from the New England Primer.

Emily Dickinson, and Ralph W. Franklin, The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Variorum Edition (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1998), 99.

1859

Emily and Susan had an editorial exchange over the second stanza of this poem, for which Dickinson supplied several drafts. Of this version, Susan wrote, “I am not suited, dear Emily with the second verse – It is remarkable as the chain lightening that blinds us hot nights in the Southern sky but it does not go with the ghostly shimmer of the first verse as well as the other one.”

Emily Dickinson, Ellen Louise Hart, and Martha Nell Smith, Open Me Carefully: Emily Dickinson’s Intimate Letters to Susan Huntington Dickinson, (Middletown, CT: Paris Press/Wesleyan University Press, 1998), 98.

- “You love me – you are sure” (Fr218)

1861

This poem includes a reference to “Dollie,” which was a pet name Emily frequently used for Sue in poems and letters. A copy may have been sent to Sue though it is not known.

Emily Dickinson, and Ralph W. Franklin, 245.

- “Is it true, dear Sue?” (Fr189)

1861

Written after the birth of Ned in 1861, this poem references life in The Evergreens alongside Emily’s complicated feelings about pregnancy and birth. “Toby” was the Dickinsons’ cat and the mentioned “Coffee cup” was likely a reference to Sue’s love of coffee.

Emily Dickinson, Ellen Louise Hart, and Martha Nell Smith, 96.

1862

A variation of this poem was sent to Sue with the first line “I showed her Hights she never saw” and the replacement of pronouns throughout the rest of the poem. Dickinson was known to occasionally shift pronoun use in her poems, changing the subject and meaning.

Emily Dickinson, and Ralph W. Franklin, 371.

- “I could not drink it, Sweet” (Fr816)

1864

In a version of this poem sent to Susan, “Sweet” was changed to “Sue.”

Emily Dickinson, and Ralph W. Franklin, 770 – 771.

- “What mystery pervades a well!” (Fr1433)

1877

The last two stanzas of this poem were sent to Sue, with the word “nature” replaced with “Susan.”

Emily Dickinson, and Ralph W. Franklin, The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Variorum Edition (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1998),1253 – 1255.

- “To own a Susan of my own” (Fr1436)

1877

The letters Emily wrote to Susan while she was away teaching in Baltimore show how strongly Emily valued having Sue near to her. In one letter from 1852 Emily writes, “If you were here, and Oh that you were, my Susie, we need not talk at all, our eyes would whisper for us, and your hand fast in mine, we would not ask for language – I try to bring you nearer.” As the two grew older, Susan’s time was increasingly occupied with her marriage, her children, and her busy social life in Amherst.

Emily Dickinson, Ellen Louise Hart, and Martha Nell Smith, Open Me Carefully: Emily Dickinson’s Intimate Letters to Susan Huntington Dickinson, 33.

1884

Having met in school as young girls, Emily and Susan shared a lifetime of memories together, remaining close until Emily’s death in 1886. In her analysis of the poem, Ellen Louis Hart sees it as a “culminating moment in a lifetime of correspondence,” in a relationship that was “constant rather than stable.”

This letter poem is introduced with the lines:

Morning

might come

by Accident –

Sister –

Night comes

by Event –

To believe the

final line of

the Card would

foreclose Faith –

Faith is Doubt.

Emily Dickinson, and Ralph W. Franklin, The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Variorum Edition (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1998),1452.

Ellen Louis Hart, “The Encoding of Homoerotic Desire: Emily Dickinson’s Letters and Poems to Susan Dickinson,” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature, vol.9 no. 2 (Autumn, 1990), 251-272.