“My Shaggy Ally”

– Emily Dickinson to T. W. Higginson, February 1863 (L280)

Newfoundland Dog. Painted by Col. H. Smith, eng. Lizars

Carlo was Edward Dickinson’s gift to Emily, his eldest daughter, in the fall of 1849, presumably to accompany her on the long walks she enjoyed in the woods and fields of Amherst. Apparently a brown Newfoundland (perhaps a curly-coated Lesser Newfoundland, for Dickinson once jokingly sent one of the dog’s tawny curls to a friend purporting it to be her own), Carlo may have been procured from family friends, the Huntingtons, who raised litters of the massive breed at their farm on the Connecticut River in Hadley. If so, it adds wit to Dickinson’s naming Carlo after the pointer of St. John Rivers in her favorite novel at the time, Jane Eyre.

Other novels soon featured dogs named Carlo – Ik Marvel’s Reveries of a Bachelor, Elizabeth Gaskell’s Cranford Rise – and by 1858 five dogs named Carlo were registered in Amherst, including another Newfoundland owned by local photographer J.L. Lovell. The breed, known for its friendly, inquisitive intelligence, enjoyed popularity among the Romantics, and was a favorite of authors whom Dickinson admired – Byron, Scott, Dickens, and Robert Burns among them. Harriet Beecher Stowe included a Newfoundland named Bruno in Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Dickinson’s first written mention of her “mute confederate” occurred in an 1850 valentine that was published by the Amherst College student magazine, The Indicator.

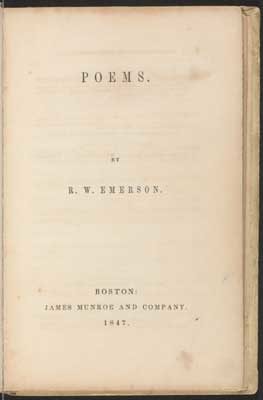

Thereafter she spoke often of Carlo in several dozen letters and even in a few poems, usually with homely humor, and always with affection and respect. She delighted that Major Edward B. Hunt, watching Carlo snap up a bit of fallen cake at the Commencement Tea in 1860, believed her dog “understood gravitation” (L342b). In April 1862, she introduced Carlo to her friend Thomas Wentworth Higginson by letter, saying, “You ask of my Companions. Hills – sir – and the Sundown, and a Dog large as myself, that my Father bought me -” (L261). It seems clear from her commentary that Carlo provided the poet great psychological comfort over the years, while her dependence on his protective presence can be gauged by her marked reclusivity once he was gone.

Neighbors described Dickinson coming to call with her outsize dog beside her. One remembered Dickinson saying to her when, as a child, she walked with the poet and her “huge dog”: “Gracie, do you know that I believe that the first to come and greet me when I go to heaven will be this dear, faithful old friend Carlo?” (Years and Hours, Vol. II, p. 21).

When Carlo died at about age 17 in January 1866, Dickinson announced his death in a terse letter to Higginson: “Carlo died. / E. Dickinson / Would you instruct me now?” (L314). Months later, still feeling his absence, she paid him this tribute:

Time is a test of trouble

But not a remedy –

If such it prove, it prove too

There was no malady.

(Fr861)

Work cited:

The Years and Hours of Emily Dickinson, ed. Jay Leyda, Vol. I, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1960