“I am glad there are Books. They are better than Heaven, for that is unavoidable, while one may miss these.”

– Emily Dickinson to F. B. Sanborn, about 1873 (L402)

For Emily Dickinson books were vehicles of the imagination – she defined them variously in poems as a “Frigate,” a “Bequest of Wings,” and “the Chariot / That bears the Human soul,” while those she loved best became her “Kinsmen of the Shelf.” She was born into a book-loving household and became a voracious reader who read widely, well beyond the well-stocked libraries of the Homestead and her brother Austin’s home next door.

For Emily Dickinson books were vehicles of the imagination – she defined them variously in poems as a “Frigate,” a “Bequest of Wings,” and “the Chariot / That bears the Human soul,” while those she loved best became her “Kinsmen of the Shelf.” She was born into a book-loving household and became a voracious reader who read widely, well beyond the well-stocked libraries of the Homestead and her brother Austin’s home next door.

In childhood, aside from her schoolbooks, she read the Bible, and was given carefully chosen, principally moralistic, Sabbath School stories by her parents and relatives. Sometime later, a young man studying in her father’s law office slipped one of Lydia Maria Child’s historical novels into the Dickinson children’s hands. “This then is a book! And there are more of them,” was her ecstatic response (L342b). Her youth was the hey-day of the Romantic literary era, with Washington Irving and Sir Walter Scott, Byron and Wordsworth, Longfellow and Tennyson at the height of popularity, not to mention the novels of Dickens and a host of minor novelists whose now forgotten titles provided popular girlhood reading. In 1848 the novels of the Brontës launched a new era of psychological fiction, much of it by women, which captured Dickinson’s sensibilities, and initiated her particular love, in turn, for the works of poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning and novelist George Eliot.

In her early twenties, discussing books was Dickinson’s stock in trade with the Amherst students and tutors who were her friends and among whom circulated books by Thomas De Quincey, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Thomas Carlyle, and German novelist Jean Paul Richter. Dickinson belonged to a reading group of Amherst young people who tackled reading Shakespeare aloud, and she was introduced to Emerson’s work by his first book of poems, a gift from her early mentor Benjamin Franklin Newton. Friendships of early adulthood, such as that with Amherst student Henry Vaughn Emmons, enlarged her awareness of and access to books beyond her own home shelves. While her father might prefer “lonely & rigorous books” (L342a) and spurn the authors his eldest daughter preferred as “modern Literati” (L113), he seems always to have purchased any books she asked for.

In addition, Dickinson kept up with current events through the daily reading of The Springfield Republican, perhaps New England’s best political and literary newspaper. She read every issue of sister-in-law Susan Dickinson’s subscription to The Atlantic Monthly, in addition to perusing a range of other periodicals that came to the Homestead, so that her gradual reclusiveness in no way interfered with knowing what was going on in the world, particularly the world of books.

Of all the literature that Dickinson devoured, the one book to which she returned again and again was the King James Bible. She read and reread it, often quoting it from memory. Its stories and personages made frequent appearances in her letters and poems, sometimes through the deftest of references. She once told a friend that all literature might be sifted to the Bible and Shakespeare.

A vital ally in the poet’s love of books, Susan Dickinson was an astonishing book acquirer for her time and equally enamored of the Brownings, Tennyson, Ruskin, and other Romantics. Sue had a taste for religious philosophers, such as Francis Quarles and Thomas à Kempis, books that became essential to the poet as well. Susan and Emily shared Sue’s library; their markings of favorite passages with light pencil strokes provides a guide to the books and authorial insights that interested them most.

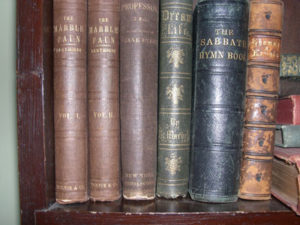

Today the libraries of the Dickinson houses are in the possession of two major universities. Many books from the Homestead are in the Houghton Library at Harvard, and the majority of those from The Evergreens are in the John Hay Library at Brown. The Museum has begun a program, called “Replenishing the Shelves,” to replace the hundreds of nineteenth-century titles that once occupied the family bookcases and were important to the poet and her family members.

Further reading:

Capps, Jack. Emily Dickinson’s Reading 1836-1886. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1966.

Sewall, Richard B. The Life of Emily Dickinson. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1974. See especially Chapter 28, “Books and Reading,” 668-705.

Heginbotham, Eleanor. “‘What Are You Reading Now?’: Emily Dickinson’s Epistolary Book Club.” Reading Emily Dickinson’s Letters: Critical Essays. Eds. Eberwein, Jane Donahue, Cindy MacKenzie and Marietta Messmer. Amherst, MA: U of Massachusetts P, 2009. xiii, 293 pp. Print.

Deppman, Jed. “Through the Dark Sod: Trying to Read with Emily Dickinson.” In Trying to Think with Emily Dickinson, 150-83. University of Massachusetts Press, 2008. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5vk41f.10.

Finnerty, Páraic. ““Shakespeare Always and Forever”: Dickinson’s Circulation of the Bard.” In Emily Dickinson’s Shakespeare, 117-39. University of Massachusetts Press, 2006. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5vk963.10.

Miller, Cristanne. Reading in Time : Emily Dickinson in the Nineteenth Century. Amherst : University of Massachusetts Press, 2012.