Emily Dickinson’s material legacy consists of about 2500 poem manuscripts and about 1000 letter manuscripts. For many poems Dickinson left more than one copy. She may have recorded it in a fascicle and also sent a copy to a friend, or she may have sent a copy to more than one recipient.

For other poems, no manuscript in Dickinson’s hand survives. Scholars must rely on transcripts of poems and letters made by others (such as her Norcross cousins) from the now-lost manuscripts.

Dickinson’s existing letters are thought to represent only about a tenth of her correspondence, but the range and scope of the surviving letters give scholars useful insights into her composition practice.

Fascicles and Other Methods of Recording Poetry

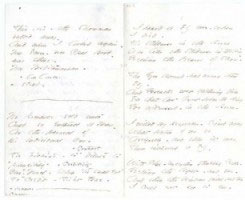

During Dickinson’s intense writing period (1858-1864), she copied more than 800 of her poems into small booklets, forty in all, now called “fascicles.” Dickinson made the small volumes herself from folded sheets of paper that she stacked and then bound by stabbing two holes on the left side of the paper and tying the stacked sheets with string.

Among her papers were fifteen unbound gatherings of poems, which scholar R. W. Franklin terms “sets.” The sets contain about 250 poems.

In addition to the fascicles and sets, Dickinson had other methods of recording her poetry. Dickinson sometimes copied poems onto individual sheets of paper. Folds in the paper may suggest that Dickinson intended to send it to a recipient but for whatever reason decided not to. R. W. Franklin refers to these as “record” or “retained” copies.

Poems in Letters

Poems in Letters

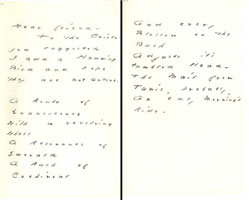

Dickinson shared about 500 of her poems with more than forty correspondents. She was particularly generous with her sister-in-law Susan Huntington Gilbert Dickinson; her correspondent Thomas Wentworth Higginson; her cousins Frances and Louisa Norcross; and family friend Samuel Bowles, editor of the Springfield Republican.

This private form of distribution seems to have appealed to the poet more than did formal publication. Sometimes she sent the same poem to more than one reader, as in the example of “A Route of Evanescence,” which she shared with at least six recipients.

The format of the poems in letters varied. Often the poems were sent with a letter on separate sheets of paper. At other times Dickinson introduced the poem with a note on the same page. In still other cases, the line between letter and poem is more difficult to distinguish.

Worksheets/Fragments

Worksheets/Fragments

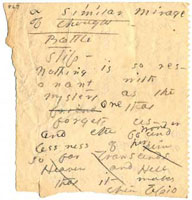

Among the most intriguing documents that Dickinson left to posterity are about 100 fragments or scraps. Some contain prose; others, poetry; some are without genre, what Dickinson scholar Marta Werner calls “extrageneric.” The papers are both literally scraps—torn or reused paper—and, more figuratively, fragments of partial ideas or less finished poems than appear in fascicles or other retained manuscripts.