“one of the most industrious and persevering men that I ever saw”

– Edward Hitchcock, President of Amherst College, on Samuel Fowler Dickinson.

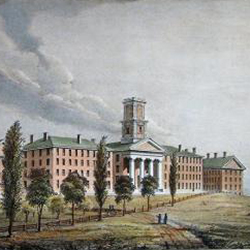

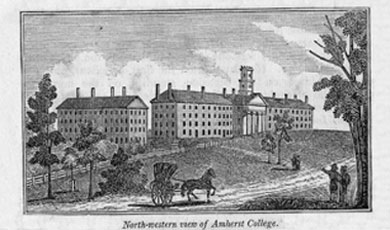

College Row, Amherst College, ca. 1830

Samuel Fowler Dickinson and Lucretia Gunn Dickinson were Emily Dickinson’s paternal grandparents. Fowler, or “Squire,” his honorary title, was a prominent Amherst lawyer, and a man of rare public spirit. Though his life overlapped with Emily’s for only a short time, Fowler Dickinson built a brick house on Main Street that would become Emily’s home and sanctuary for most of her life.

A deeply religious man, Squire Dickinson became deacon of the church in 1798 at the unusually young age of 23. A farmer and major land-owner in the country, he served the community into which he had been born with legendary determination and energy. He was Town Clerk, served twelve years as a state Representative (1803-1827), and spent one as a Senator (1828). He planted trees. He represented the town in legal matters. Edward Hitchcock, President of Amherst College from 1845 to 1854, recalled Fowler as “one of the most industrious and persevering men that I ever saw” (Reminiscences of Amherst College, Northampton, Mass.: Bridgman & Childs, 1863, p. 5). Lucretia Gunn of Montague, whom Fowler married in 1802, kept their home, raised nine children, and supported her husband’s work.

A driving force behind the creation of Amherst Academy in 1814, Fowler Dickinson was one of the first to subscribe to the charitable fund that served as the foundation for Amherst College (opened in 1821). He expressed his fervent belief in the virtue of education for both sexes, evident in the admission policy of the Academy, in a public address in 1831:

“A good husbandman will also educate well his daughters…daughters should be well instructed in the useful sciences; comprising a good English education: including a thorough knowledge of our own language, geography, history, mathematics and natural philosophy. The female mind, so sensitive, so susceptible of improvement, should not be neglected….God hath designed nothing in vain.” (address given to the Hampshire, Hampden and Franklin Agricultural Society on October 27, 1831, in Northampton, Massachusetts. Cited in The Years and Hours of Emily Dickinson, ed. Jay Leyda, Vol. I, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1960, pp.17-18)

His support of these educational endeavors came at great personal cost. By 1833, he was bankrupt. Fowler had “sacrificed his property, his time and his professional opportunities” for the College (The History of the Town of Amherst, Massachusetts, Amherst: Carpenter & Morehouse, 1896, p. 187). Although his son Edward, the poet’s father, tried to mitigate the situation by purchasing half of the family’s Homestead, eventually Fowler Dickinson was forced to leave Amherst with his wife and two youngest daughters and move to Cincinnati, where he became Steward of the Lane Theological Seminary. He later served as Treasurer of Western Reserve College in Hudson, Ohio. By April 22, 1838 he was dead of “lung fever” at age 62.

His Ohio obituary, reprinted in the Hampshire Gazette on June 6, 1838 noted: “…his piety consisted much in a deep laid principle of active, yet meek and unostentatious beneficence. The grand practical maxim of his life seemed to be to ‘esteem others better than himself’—to lead him to neglect his own interests, and attempt to make all others within his sphere comfortable and happy” (Leyda, Vol. I, p. 49).

After her husband’s death, Lucretia returned east. She died in Enfield, Massachusetts, on May 11, 1840. Both Samuel Fowler and Lucretia Gunn Dickinson were reinterred in the family plot in the Amherst burying ground in the 1840s.

Samuel Fowler Dickinson and Lucretia Gunn Dickinson’s most lasting legacy for their granddaughter was the home she lived in, the academy she attended as a child, and the college that was her family’s community for decades.